Testing in React

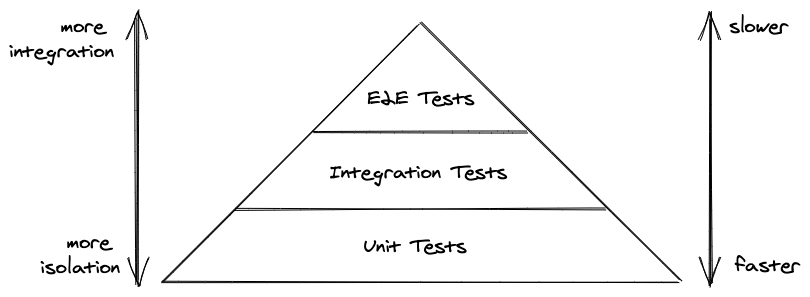

Testing source code is an essential part of programming and should be seen as a mandatory exercise for serious developers. The goal is to verify our source code's quality and functionality before using it in production. The testing pyramid will serve as our guide.

The testing pyramid includes end-to-end tests, integration tests, and unit tests. Unit tests are for small, isolated blocks of code, such as a single function or component. Integration tests help us figure out how well these blocks of code work together. And end-to-end tests simulate a real-life scenario, like a user logging into a web application. While unit tests are quick and easy to write and maintain; end-to-end tests are the opposite.

Many unit tests are required to cover all the functions and components in a working application, after which several integration tests make sure that the most important units work together. The final touch give a few end-to-end tests to simulate critical user scenarios. In this section, we will cover unit and integration tests, in addition to a useful component-specific testing technique called snapshot tests. E2E tests will be part of the exercise.

Choosing a testing library can be a challenge for React beginners, as there are many options. To keep things simple, we'll employ the most popular tools: Vitest and React Testing Library (RTL). Vitest is a full-blown testing framework with test runners, test suites, test cases, and assertions. RTL is used for rendering React components, triggering events like mouse clicks, and selecting HTML elements from the DOM to perform assertions. We'll explore both tools step-by-step, from setup to unit testing to integration testing.

Before we can write our first test, we have to install Vitest and set it up. Start by typing the following instruction on the command line:

Command Line

npm install vitest --save-devThen in your package.json file, add another script which will run the tests eventually:

package.json

"dev": "vite",

"build": "vite build",

"test": "vitest",

"lint": "eslint .",

"preview": "vite preview"Last, create a new file for testing functions and components:

Command Line

touch src/App.test.jsxFrom there we will start writing tests for features that come from the src/App.jsx file next to it.

Test Suites, Test Cases, and Assertions

Test suites and test cases are commonly used in JavaScript and many other programming languages. A test suite groups the individual test cases into one larger subject. Let's see how this looks with Vitest in our src/App.test.jsx file:

src/App.test.jsx

import { describe, it, expect } from 'vitest';

describe('something truthy and falsy', () => {

it('true to be true', () => {

expect(true).toBe(true);

});

it('false to be false', () => {

expect(false).toBe(false);

});

});The "describe" block is our test suite, and the "it" blocks are our test cases. Note that test cases can be used without test suites:

Code Playground

import { it, expect } from 'vitest';

it('true to be true', () => {

expect(true).toBe(true);

});

it('false to be false', () => {

expect(false).toBe(false);

});Large subjects like functions or components often require multiple test cases, so it makes sense to use them with test suites:

Code Playground

describe('App component', () => {

it('removes an item when clicking the Dismiss button', () => {

});

it('requests some initial stories from an API', () => {

});

});Finally you can run tests using the test script from your package.json on the command line with npm run test to produce the following output:

Command Line

✓ src/App.test.jsx (2)

✓ something truthy and falsy (2)

✓ true to be true

✓ false to be false

Test Files 1 passed (1)

Tests 2 passed (2)

Start at 13:19:38

Duration 122msWhen we run the test command, the test runner matches all files with a test.jsx suffix. Successful tests are displayed in green, failed tests in red. The interactive test script watches your tests and source code and executes tests when the files change. Vitest also provides a few interactive commands (press "h" to see all of them), such as pressing "f" to run failed tests and "a" for running all tests. Let's see how this looks for a failed test:

src/App.test.jsx

import { describe, it, expect } from 'vitest';

describe('something truthy and falsy', () => {

it('true to be true', () => {

expect(true).toBe(true);

});

it('false to be false', () => {

expect(false).toBe(true);

});

});The tests run again, and the command line output shows a failed test in red:

Command Line

AssertionError: expected false to be true // Object.is equality

- Expected

+ Received

- true

+ false

src/App.test.jsx:9:19

7|

8| it('false to be false', () => {

9| expect(false).toBe(true);

| ^

10| });

11| });

Test Files 1 failed (1)

Tests 1 failed | 1 passed (2)

Start at 13:20:44

Duration 124ms

FAIL Tests failed. Watching for file changes...

press h to show help, press q to quitFamiliarize yourself with this test output, because it shows all failed tests, as well as information on why they failed. Using this information, you can fix certain parts of your code until all tests run green. Next, we'll cover test assertions, two of which we've already used with Vitest's expect function. An assertion works by expecting value on the left side (expect) to match a value on the right side (toBe). toBe is only one of many available assertive functions provided by Vitest.

src/App.test.jsx

import { describe, it, expect } from 'vitest';

describe('something truthy and falsy', () => {

it('true to be true', () => {

expect(true).toBeTruthy();

});

it('false to be false', () => {

expect(false).toBeFalsy();

});

});Once you start testing, it's a good practice to keep two command line interfaces open: one for watching your tests (npm run test) and one for developing your application (npm run dev). If you are using source control like git, you may want to have even one more command line interface for adding your source code to the repository.

Exercises:

- Compare your source code against the author's source code.

- Recap all the source code changes from this section.

- Read more about Vitest.

Unit Testing: Functions

A unit test is generally used to test components or functions in isolation. For functions, unit tests are for input and output; for components, we test props, callback handlers communicating to the outside, or the output of the components. Before we can perform a unit test on our src/App.jsx file, we must export components and functions like the reducer from our src/App.jsx file with a named export:

src/App.jsx

...

export default App;

export { storiesReducer, SearchForm, InputWithLabel, List, Item };The exercises at the end of this chapter will cover all the remaining tests you should consider performing. For now, we can import all the components and reducers in our src/App.test.jsx file and we will focus on the reducer test first. We are also importing React here, because we have to include it whenever we test React components:

src/App.test.jsx

import { describe, it, expect } from 'vitest';

import App, {

storiesReducer,

Item,

List,

SearchForm,

InputWithLabel,

} from './App';Before we unit test our first React component, we'll cover how to test just a JavaScript function. The best candidate for this test use case is the storiesReducer function and one of its actions. Let's define some test data and the test suite for the reducer test:

src/App.test.jsx

...

const storyOne = {

title: 'React',

url: 'https://react.dev/',

author: 'Jordan Walke',

num_comments: 3,

points: 4,

objectID: 0,

};

If you extrapolate the test cases, there should be one test case per reducer action. We will focus on a single action, which you can use to perform the rest as exercise yourself. The reducer function accepts a state and an action, and then returns a new state, so all reducer tests essentially follow the same pattern:

src/App.test.jsx

...

describe('storiesReducer', () => {

it('removes a story from all stories', () => {

const action = // TODO: some action

const state = // TODO: some current state

For our case, we define action, state, and expected state according to our reducer. The expected state will have one less story, which was removed as it passed to the reducer as action:

src/App.test.jsx

describe('storiesReducer', () => {

it('removes a story from all stories', () => {

const action = { type: 'REMOVE_STORY', payload: storyOne };

const state = { data: stories, isLoading: false, isError: false };

const newState = storiesReducer(state, action);

const expectedState = {

data: [storyTwo],

isLoading: false,

isError: false,

};

expect(newState).toBe(expectedState);

});

});This test still fails because we are using toBe instead of toStrictEqual. The toBe assertive function makes a strict comparison like newState === expectedState. The content of the objects are the same, however, their object references are not the same. We use toStrictEqual instead of toBe to limit our comparison to the object's content:

src/App.test.jsx

expect(newState).toStrictEqual(expectedState);

// expect(newState).toBe(expectedState);There is always the decision to make for JavaScript objects whether you want to make a strict comparison or just a content comparison. Most often you only want to have a content comparison here, hence use toStrictEqual. For JavaScript primitives though, like strings or booleans, you can still use toBe. Also note that there is a toEqual function which works slightly different than toStrictEqual.

We continue to make adjustments until the reducer test turns green, which is really testing a JavaScript function with a certain input and expecting a certain output. We haven't done any testing regarding React components yet.

Remember, a reducer function will always follow the same test pattern: given a state and action, we expect the following new state. Every action of the reducer could be another test case in our reducer's test suite, so consider using the exercises as a way to move through your entire source code.

Exercises:

- Compare your source code against the author's source code.

- Recap all the source code changes from this section.

- Continue to write a test case for every reducer action and its state transition.

- Read more about Vitest's assertive functions like

toBeandtoStrictEqual.

Unit Testing: Components

We tested our first function in JavaScript with Vitest in the previous section. Next, we'll test our first React component in isolation with a unit test. Therefore we have to tell Vitest about the headless browser environment where we want to render React components, because the test will not start an actual browser for us. However, the HTML that's getting rendered with a React component has to end up somewhere (e.g. headless browser) to make it accessible for testing. The most popular way to perform this task is installing jsdom which acts like a headless browser for us:

Command Line

npm install jsdom --save-devThen we can include it to the Vite configuration file:

vite.config.js

import { defineConfig } from 'vite';

import react from '@vitejs/plugin-react';

// https://vitejs.dev/config/

export default defineConfig({

plugins: [react()],

test: {

environment: 'jsdom',

},

});In addition, we will render React components in tests with a library called react-testing-library (RTL). We need to install it too:

Command Line

npm install @testing-library/react @testing-library/jest-dom --save-devAfterward, we create a new file for a general testing setup:

Command Line

mkdir tests

cd tests

touch setup.jsAnd reference it in Vite's configuration file:

vite.config.js

import { defineConfig } from 'vite';

import react from '@vitejs/plugin-react';

// https://vitejs.dev/config/

export default defineConfig({

plugins: [react()],

test: {

environment: 'jsdom',

setupFiles: './tests/setup.js',

},

});Last, include the following implementation details in the new setup file for our tests:

tests/setup.js

import { expect, afterEach } from 'vitest';

import { cleanup } from '@testing-library/react';

import * as matchers from "@testing-library/jest-dom/matchers";

expect.extend(matchers);

afterEach(() => {

cleanup();

});Essentially Vitest's expect method gets extended by more methods given from RTL. We will use these methods (e.g. toBeInTheDocument) in our tests soonish. Now we can finally import the following functions from React Testing Library which are used for component tests:

src/App.test.jsx

import { describe, it, expect } from 'vitest';

import {

render,

screen,

fireEvent,

waitFor,

} from '@testing-library/react';

Start with the Item component, where we assert whether it renders all expected properties based on its given props. Based on the input (read: props), we are asserting an output (rendered HTML). We'll use RTL's render function in each test to render a React component. In this case, we render the Item component as an element and pass it an item object -- one of our previously defined stories -- as props:

src/App.test.jsx

...

const storyOne = { ... };

const storyTwo = { ... };

const stories = [storyOne, storyTwo];

describe('storiesReducer', () => {

...

});

describe('Item', () => {

it('renders all properties', () => {

render(<Item item={storyOne} />);

});

});After rendering it, we didn't do any testing yet (the tests are turning out green though, because there was no failed test in the test file), so we can use the debug function from RTL's screen object to output on the command line what has been rendered in jsdom's environment:

src/App.test.jsx

describe('Item', () => {

it('renders all properties', () => {

render(<Item item={storyOne} />);

screen.debug();

});

});Run the tests with npm run test, and you'll see the output from the debug function. It prints all your component's and child component's HTML elements. The output should be similar to the following:

Command Line

<body>

<div>

<li>

<span>

<a

href="https://reactjs.org/"

>

React

</a>

</span>

<span>

Jordan Walke

</span>

<span>

3

</span>

<span>

4

</span>

<span>

<button

type="button"

>

Dismiss

</button>

</span>

</li>

</div>

</body>Here you should form the habit of using RTL's debug function whenever you render a new component in a React component test. The function gives a useful overview of what is rendered and informs the best way to proceed with testing. Based on the current output, we can start with our first assertion. RTL's screen object provides a function called getByText, one of many search functions:

src/App.test.jsx

describe('Item', () => {

it('renders all properties', () => {

render(<Item item={storyOne} />);

expect(screen.getByText('Jordan Walke')).toBeInTheDocument();

expect(screen.getByText('React')).toHaveAttribute(

'href',

'https://react.dev/'

);

});

});For the two assertions, we use the two assertive functions toBeInTheDocument and toHaveAttribute (both needed the expect extension from the tests/setup.js file). These are to verify an element with the text "Jordan Walke" is in the document, and the presence of an element with the text "React" with a specific href attribute value. Over time, you will see more of these assertive functions being used.

RTL's getByText search function finds the one element with the visible texts "Jordan Walke" and "React". We can use the getAllByText equivalent to find more than one element. Similar equivalents exist for other search functions.

The getByText function returns the element with a text that users can see, which relates to the real-world use of the application. Note that getByText is not the only search function, though. Another highly-used search function is the getByRole or getAllByRole function:

src/App.test.jsx

describe('Item', () => {

it('renders all properties', () => {

...

});

it('renders a clickable dismiss button', () => {

render(<Item item={storyOne} />);

The getByRole function is usually used to retrieve elements by aria-label attributes. However, there are also implicit roles on HTML elements -- like "button" for a button HTML element. Thus you can select elements not only by visible text, but also by their (implicit) accessibility role with React Testing Library. A neat feature of getRoleBy is that it suggests roles if you provide a role that's not available.

src/App.test.jsx

describe('Item', () => {

it('renders all properties', () => {

...

});

it('renders a clickable dismiss button', () => {

render(<Item item={storyOne} />);

screen.getByRole('');

Which should output something similar to the following on the command line:

Command Line

TestingLibraryElementError:

Unable to find an accessible element with the role ""

Here are the accessible roles:

listitem:

Name "":

<li />

link:

Name "React":

<a

href="https://reactjs.org/"

/>

button:

Name "Dismiss":

<button

type="button"

/>Both, getByText and getByRole are RTL's most widely used search functions. We can continue here by asserting not only that everything is in the document, but also by asserting whether our events work as expected. For example, the Item component's button element can be clicked and we want to verify that the callback handler gets called. Therefore, we are using Vitest for creating a mocked function which we provide as a callback handler to the Item component. Then, after firing a click event with React Testing Library on the button, we want to assert that the callback handler function has been called:

src/App.test.jsx

import { describe, it, expect, vi } from 'vitest';

...

describe('Item', () => {

it('renders all properties', () => {

...

});

it('renders a clickable dismiss button', () => {

...

});

it('clicking the dismiss button calls the callback handler', () => {

const handleRemoveItem = vi.fn();

Vitest lets us pass a test-specific function to the Item component as a prop. These test-specific functions are called spy, stub, or mock; each is used for different test scenarios. The vi.fn() returns us a mock for the actual function, which lets us capture when it's called. As a result, we can use Vitest's assertions like toHaveBeenCalledTimes, which lets us assert a number of times the function has been called; and toHaveBeenCalledWith, to verify arguments that are passed to it.

Every time we want to mock a JavaScript function, whether it has been called or whether it received certain arguments, we can use Vitest's helper function to create a mocked function. Then, after invoking this function with RTL's fireEvent object's function, we can assert that the provided callback handler -- which is the mocked function -- has been called one time.

In the last exercise we tested the Item component's input and output via rendering assertions and callback handler assertions. We are not testing real state changes yet, however, as there is no actual item removed from the DOM after clicking the "Dismiss"-button. The logic to remove the item from the list is in the App component, but we are only testing the Item component in isolation. Sometimes it's just useful to test whether a single block works, before testing everything all together. We will test the actual implementation logic for removing an Item when we cover the App component later.

For now, the SearchForm component uses the InputWithLabel component as a child component. We will make this to our next test case. As before, we will start by rendering the component, here the parent component, and providing all the essential props:

src/App.test.jsx

...

describe('SearchForm', () => {

const searchFormProps = {

searchTerm: 'React',

onSearchInput: vi.fn(),

searchAction: vi.fn(),

};

Again, we start with the debugging. After evaluating what renders on the command line, we can make the first assertion for the SearchForm component. With input fields in place, the getByDisplayValue search function from RTL is the perfect candidate to return the input field as an element:

src/App.test.jsx

describe('SearchForm', () => {

const searchFormProps = { ... };

it('renders the input field with its value', () => {

render(<SearchForm {...searchFormProps} />);

expect(screen.getByDisplayValue('React')).toBeInTheDocument();

});

});Since the HTML input element is rendered with a default value, we can use the default value (here: "React"), which is the displayed value in our test assertion. If the input element doesn't have a default value, the application could show a placeholder with the placeholder HTML attribute on the input field. Then we'd use another function from RTL called getByPlaceholderText, which is used for searching an element with a placeholder text.

Because the debug information presented multiple options to query the HTML, we could continue with one more test to assert the rendered label:

src/App.test.jsx

describe('SearchForm', () => {

const searchFormProps = { ... };

it('renders the input field with its value', () => {

...

});

it('renders the correct label', () => {

render(<SearchForm {...searchFormProps} />);

The getByLabelText search function allows us to find an element by a label in a form. This is useful for components that render multiple labels and HTML controls. However, you may have noticed we used a regular expression here. If we used a string instead, the colon for "Search:" must be included. By using a regular expression, we are matching strings that include the "Search" string, which makes finding elements much more efficient. For this reason, you may find yourself using regular expressions instead of strings quite often.

Anyway, perhaps it would be more interesting to test the interactive parts of the SearchForm component. Since our callback handlers, which are passed as props to the SearchForm component, are already mocked with Vitest, we can assert whether these functions get called appropriately:

src/App.test.jsx

describe('SearchForm', () => {

const searchFormProps = {

searchTerm: 'React',

onSearchInput: vi.fn(),

searchAction: vi.fn(),

};

...

it('calls onSearchInput on input field change', () => {

render(<SearchForm {...searchFormProps} />);

Similar to the Item component, we tested input (props) and output (callback handler) for the SearchForm component. The difference is that the SearchForm component renders a child component called InputWithLabel. If you check the debug output, you'll likely notice that React Testing Library just renders the whole component tree for both components. This happens because the end-user wouldn't care about the component tree either, but only about the HTML that is getting displayed. So the React Testing Library outputs all the HTML that matters for the user and thus the test.

All the callback handler tests for Item and SearchForm component verify only whether the functions have been called. No React re-rendering occurs, because all the components are tested in isolation without state management, which solely happens in the App component. Real testing with RTL starts further up the component tree, where state changes and side-effects can be evaluated. Therefore, let me introduce integration testing next.

Exercises:

- Compare your source code against the author's source code.

- Recap all the source code changes from this section.

- Read more about React Testing Library.

- Read more about search functions.

- Use

toHaveBeenCalledWithnext totoHaveBeenCalledTimesto make your assertions more bullet proof. - Add tests for your List and InputWithLabel components.

Integration Testing: Component

React Testing Library adheres to a single core philosophy: instead of testing implementation details of React components, it tests how users interact with the application and if it works as expected. This becomes especially powerful for integration tests.

We'll need to provide some data before we test the App component, since it makes requests for data from a remote API after its initial render. Because we are using axios for the data fetching in the App component, we'll have to mock it with Vitest at the top of the testing file:

src/App.test.jsx

...

import axios from 'axios';

...

vi.mock('axios');

...Next, implement the data you want to be returned from the mocked API request with a JavaScript Promise, and use it for the axios mock. Afterward, we can render our component and assume the correct data is mocked for our API request:

src/App.test.jsx

...

describe('App', () => {

it('succeeds fetching data', () => {

const promise = Promise.resolve({

data: {

hits: stories,

},

});

Now we'll use React Testing Library's waitFor helper function to wait until the promise resolves after the component's initial render. With async/await, we can implement this like synchronous code. The debug function from RTL is useful because it outputs the App component's elements before and after the request:

src/App.test.jsx

describe('App', () => {

it('succeeds fetching data', async () => {

const promise = Promise.resolve({

data: {

hits: stories,

},

});

axios.get.mockImplementationOnce(() => promise);

render(<App />);

screen.debug();

await waitFor(async () => await promise);

In the debug's output, we see the loading indicator renders for the first debug function, but not the second. This is because the data fetching and component re-render complete after we resolve the promise in our test with waitFor. Let's assert the loading indicator for this case:

src/App.test.jsx

describe('App', () => {

it('succeeds fetching data', async () => {

const promise = Promise.resolve({

data: {

hits: stories,

},

});

axios.get.mockImplementationOnce(() => promise);

render(<App />);

expect(screen.queryByText(/Loading/)).toBeInTheDocument();

await waitFor(async () => await promise);

expect(screen.queryByText(/Loading/)).toBeNull();

});

});Because we're testing for a returned element that is absent, this time we use RTL's queryByText instead of the getByText function. Using getByText in this instance would produce an error, because the element can't be found; but with queryByText the value just returns null.

Again, we're using a regular expression /Loading/ instead of a string 'Loading'. To use a string, we'd have to explicitly use 'Loading ...' instead of 'Loading'. With a regular expression, we don't need to provide the whole string, we just need to match a part of it.

Next, we can assert whether or not our fetched data gets rendered as expected:

src/App.test.jsx

describe('App', () => {

it('succeeds fetching data', async () => {

const promise = Promise.resolve({

data: {

hits: stories,

},

});

axios.get.mockImplementationOnce(() => promise);

render(<App />);

expect(screen.queryByText(/Loading/)).toBeInTheDocument();

await waitFor(async () => await promise);

expect(screen.queryByText(/Loading/)).toBeNull();

expect(screen.getByText('React')).toBeInTheDocument();

expect(screen.getByText('Redux')).toBeInTheDocument();

expect(screen.getAllByText('Dismiss').length).toBe(2);

});

});The happy path for the data fetching is tested now. Similarly, we can test the unhappy path in case of a failed API request. The promise needs to reject and the error should be caught with a try/catch block:

src/App.test.jsx

describe('App', () => {

it('succeeds fetching data', async () => {

...

});

it('fails fetching data', async () => {

const promise = Promise.reject();

There may be some confusion about when to use getBy or the queryBy search variants. As a rule of thumb, use getBy for single elements, and getAllBy for multiple elements. If you are checking for elements that aren't present, use queryBy (or queryAllBy). In this code, I preferred using queryBy for the sake of alignment and readability.

Now we know the initial data fetching works for our App component, so we can move to testing user interactions. We have only tested user actions in the child components thus far, by firing events without any state and side-effect. Next, we'll remove an item from the list after the data has been fetched successfully. Since the item with "Jordan Walke" is the first rendered item in the list, it gets removed if we click the first "Dismiss"-button:

src/App.test.jsx

describe('App', () => {

...

it('removes a story', async () => {

const promise = Promise.resolve({

data: {

hits: stories,

},

});

To test the search feature, we set up the mocking differently, because we're handling initial request, plus another request once the user searches for more stories by a specific search term:

src/App.test.jsx

describe('App', () => {

...

it('searches for specific stories', async () => {

const reactPromise = Promise.resolve({

data: {

hits: stories,

},

});

Instead of mocking the request once with Vitest (mockImplementationOnce), now we mock multiple requests (mockImplementation). Depending on the incoming URL, the request either returns the initial list ("React"-related stories), or the new list ("JavaScript"-related stories). If we provide an incorrect URL to the request, the test throws an error for confirmation. As before, let's render the App component:

src/App.test.jsx

describe('App', () => {

...

it('searches for specific stories', async () => {

const reactPromise = Promise.resolve({ ... });

const anotherStory = { ... };

const javascriptPromise = Promise.resolve({ ... });

axios.get.mockImplementation((url) => {

...

});

// Initial Render

We are resolving the first promise for the initial render. We expect the input field to render "React", and the two items in the list to render the creators of React and Redux. We also make sure that no stories related to JavaScript are rendered yet. Next, change the input field's value by firing an event, and asserting that the new value is rendered from the App component through all its child components in the actual input field:

src/App.test.jsx

describe('App', () => {

...

it('searches for specific stories', async () => {

...

expect(screen.queryByText('Jordan Walke')).toBeInTheDocument();

expect(

screen.queryByText('Dan Abramov, Andrew Clark')

).toBeInTheDocument();

expect(screen.queryByText('Brendan Eich')).toBeNull();

// User Interaction -> Search

Lastly, we can submit this search request by firing a submit event with the button. The new search term is used from the App component's state, so the new URL searches for JavaScript-related stories that we have mocked before:

src/App.test.jsx

describe('App', () => {

...

it('searches for specific stories', async () => {

...

expect(screen.queryByDisplayValue('React')).toBeNull();

expect(

screen.queryByDisplayValue('JavaScript')

).toBeInTheDocument();

fireEvent.click(screen.queryByText('Submit'));

Brendan Eich is rendered as the creator of JavaScript, while the creators of React and Redux are removed. This test depicts an entire test scenario in one test case. We can move through each step -- initial fetching, changing the input field value, submitting the form, and retrieving new data from the API -- with the tools we've used.

React Testing Library with Vitest is the most popular library combination for React testing. RTL provides relevant testing tools, while Vitest has a general testing framework for test suites, test cases, assertions, and mocking capabilities. If you need an alternative to RTL, consider trying Enzyme by Airbnb.

Exercises:

- Compare your source code against the author's source code.

- Recap all the source code changes from this section.

- Read more about React Testing Library in React.

- Read more about E2E tests in React.

- While you continue with the upcoming sections, keep your tests green and add new tests when needed.

Snapshot Testing

Snapshot tests as a more lightweight way to test React components and their structure. Essentially a snapshot test creates an instance of your rendered component's output as HTML elements and their structure. This snapshot is compared to the same snapshot in the next test to give more output on how the rendered component changed and show why any tests failed in the difference. You can accept or deny any differences in your source code until the component functions as intended.

Snapshot tests are lightweight, with less focus on the implementation details of the component. Let's perform a snapshot test for our SearchForm component:

src/App.test.jsx

describe('SearchForm', () => {

...

it('renders snapshot', () => {

const { container } = render(<SearchForm {...searchFormProps} />);

expect(container.firstChild).toMatchSnapshot();

});

});Run the tests with npm run test and you'll see a new src/snapshots folder has been created in your project folder. Similar to RTL's debug function, there's a snapshot of your rendered SearchForm component as an HTML element structure in the file. Next, head to src/App.jsx file and change the HTML. For example, try removing the bold text from the SearchForm component:

src/App.jsx

const SearchForm = ({

searchTerm,

onSearchInput,

searchAction,

}) => (

<form action={searchAction}>

<InputWithLabel

id="search"

value={searchTerm}

isFocused

onInputChange={onSearchInput}

>

Search:

</InputWithLabel>

<button type="submit" disabled={!searchTerm}>

Submit

</button>

</form>

);After the next test, the command line should look similar to the following:

Command Line

- Expected - 3

+ Received + 1

<label

for="search"

>

- <strong>

- Search:

- </strong>

+ Search:

</label>

Snapshots 1 failedThis is a typical case for a breaking snapshot test. When a component's HTML structure is changed unintentionally, the snapshot test informs us on the command line. To fix it, we would go into the src/App.jsx file and edit the SearchForm component. For intentional changes, press "u" on the command line for interactive tests and a new snapshot will be created. Try it and see how the snapshot file in your src/snapshots folder changes.

Vitest stores snapshots in a folder so it can validate the difference against future snapshot tests. Users can share these snapshots across teams using version control platforms like git. This is how we make sure the DOM stays the same.

Snapshot tests are useful for setting up tests quickly in React, though it's best to avoid using them exclusively. Instead, use snapshot tests for components that don't update often, are less complex, and where it's easier to compare component results.

Exercises:

- Compare your source code against the author's source code.

- Recap all the source code changes from this section.

- Add one snapshot test for each of all the other components and check the content of your src/snapshots/ folder.